Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester

| Robert Dudley | |

|---|---|

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, c. 1564. In the background are the devices of the Order of Saint Michael and the Order of the Garter; Robert Dudley was a knight of both. |

|

| Born | 24 June 1532 |

| Died | 4 September 1588 (aged 56) Cornbury, Oxfordshire |

| Resting place | Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick |

| Title | Earl of Leicester |

| Tenure | 1564–1588 |

| Other titles | Baron of Denbigh |

| Known for | Favourite of Elizabeth I |

| Nationality | English |

| Residence | Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire Leicester House, London Wanstead, Essex |

| Locality | West Midlands North Wales |

| Wars and battles | Ket's Rebellion Campaign against Mary Tudor, 1553 Battle of St. Quentin, 1557 Dutch Revolt Spanish Armada |

| Offices | Master of the Horse Lord Steward of the Royal Household Privy Councillor Governor-General of the United Provinces |

| Spouse(s) | Amy Robsart Lettice Knollys |

| Issue | Sir Robert Dudley (illegitimate) Robert Dudley, Lord Denbigh (died as a child) |

| Parents | John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland Jane Guildford |

| Signature | |

|

|

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester KG (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English nobleman, and the favourite and close friend of Elizabeth I of England from her first year on the throne until his death. For many years he was a suitor for the Queen's hand; she giving him reason to hope.

Dudley's youth was overshadowed by the downfall of his family in 1553 after his father, the Duke of Northumberland, had unsuccessfully tried to establish Lady Jane Grey on the English throne. Robert Dudley was condemned to death but was rehabilitated with the help of Philip II of Spain, then England's king consort. On Queen Elizabeth's accession in November 1558 Dudley was appointed Master of the Horse. In October 1562 he became a privy councillor and in 1587 was appointed Lord Steward of the Royal Household. In 1564 Dudley became Earl of Leicester and from 1563 one of the greatest landowners in North Wales and the English West Midlands by royal grants.

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester was one of Elizabeth's leading statesmen, involved in domestic as well as foreign politics alongside William Cecil and Francis Walsingham. Although he adamantly refused to be married to Mary, Queen of Scots, Dudley was for a long time relatively sympathetic to her until from the mid-1580s he strongly advocated her execution. As patron of the Puritan movement he supported non-conforming preachers, but tried to mediate between them and the bishops within the Church of England. A champion also of the international Protestant cause, he led the English campaign in support of the Dutch Revolt from 1585–1587. His acceptance of the post of Governor-General of the United Provinces infuriated Queen Elizabeth. The expedition was a military and political failure and ruined the Earl financially. Leicester was engaged in many large-scale business ventures and a main backer of Francis Drake and other explorers and privateers. During the Spanish Armada the Earl was in overall command of the English land forces. In this function he invited Queen Elizabeth to visit her troops at Tilbury. This was the last of many events he organized over the years, the most spectacular being the festival at his seat Kenilworth Castle in 1575 on occasion of a three-week visit by the Queen. Dudley was a principal patron of the arts, literature, and the Elizabethan theatre.[1]

Robert Dudley's private life interfered with his court career and vice versa. When his first wife, Amy Robsart, fell down a flight of stairs and died in 1560, he was free to marry the Queen. However, the resulting scandal very much reduced his chances in this respect. Popular rumours that he had arranged for his wife's death continued throughout his life, despite the coroner's jury's verdict of accident. For eighteen years he did not remarry for Queen Elizabeth's sake and when he finally did, his new wife, Lettice Knollys, was permanently banished from court. This and the death of his only legitimate son and heir were heavy blows.[2] Shortly after the child's death in 1584 a virulent libel known as Leicester's Commonwealth was best-selling in England. It laid the foundation of a literary and historiographical tradition that often depicted the Earl as the Machiavellian "master courtier"[3] and as a deplorable figure around Elizabeth I. More recent research has led to a reassessment of his place in Elizabethan government and society.

Contents |

Youth

Education and marriage

Robert Dudley was the fifth son of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland and his wife Jane, daughter of Sir Edward Guildford.[5] The Dudleys were a large and happy family, with thirteen children born.[6] These were educated in Renaissance Humanism, having such instructors as John Dee,[7] Thomas Wilson, and Roger Ascham.[8] Roger Ascham thought that his pupil Robert had an uncommon talent for languages and writing, "exceed[ing] almost all other by nature", and regretted that he had done himself harm by preferring "Euclid's pricks and lines" (mathematics).[9] The craft of the courtier Robert learnt at the courts of Henry VIII and Edward VI.[10] "My bringing-up has been too long about Princes to misuse anything towards them", he would summarize his lessons.[11]

In 1549 Robert Dudley participated in crushing Ket's Rebellion and probably first met Amy Robsart, whom he was to wed on 4 June 1550 in the presence of the young King Edward.[12] She was of the same age as the bridegroom and the daughter and heiress of Sir John Robsart, a gentleman-farmer of Norfolk.[13] It was a love-match, and the young couple depended heavily on both their fathers' gifts, especially Robert's. John Dudley, who since early 1550 effectively ruled England, was pleased to strengthen his influence in Norfolk by his son's marriage.[14] Lord Robert, as he was styled as a duke's son, became an important local gentleman and a Member of Parliament. His court career went on in parallel.[15]

Condemned and pardoned

On 6 July 1553 King Edward VI died and the Duke of Northumberland attempted to transfer the English Crown to Lady Jane Grey, his daughter-in-law, who was married to his youngest son, Guilford Dudley.[16] Robert Dudley led a force of three hundred into Norfolk where Mary Tudor was assembling her followers. After some ten days in the county and securing several towns for Queen Jane, he took King's Lynn and proclaimed her on the market-place.[17] The next day, 19 July, the reign of Queen Jane was over in London. Soon, the townsmen of King's Lynn seized Robert Dudley and the small rest of his troop and sent him to Framlingham Castle before Queen Mary.[18]

He was imprisoned in the Tower of London, attainted, and condemned to death, as were his father and four brothers. His father went to the scaffold.[19] In the Tower, Dudley's stay coincided with the imprisonment of his childhood friend,[20] Princess Elizabeth, who had been sent there on the orders of her half-sister, the Queen. It cannot be ruled out that they met in the Tower, even if not on the leads of the Bell Tower, as popular legend would have it.[21] Yet, Robert Dudley and his brother Guilford were allowed to walk on "the leads in the Bell Tower".[22] Guilford Dudley was executed in February 1554. The surviving brothers were released in the autumn; working their release, their mother (who died in January 1555) and their brother-in-law, Henry Sidney, had befriended the Spanish nobles around the new king consort, Prince Philip of Spain.[23] Robert Dudley later frequently acknowledged that it was King Philip "to whom he owed his life".[24]

The Dudley brothers were only welcome at court as long as King Philip was there,[25] otherwise they were even suspected of associating with people who conspired against Mary's regime.[26] In January 1557 Robert and Amy Dudley were allowed to repossess some of their former lands, but Dudley was already heaping up considerable debts.[27] In March of the same year he was at Calais where he was chosen to deliver personally to Queen Mary the happy news of her husband's return to England.[28] Ambrose, Robert, and Henry Dudley, now the youngest brother, fought for Philip II at the Battle of St. Quentin in August 1557.[29] Henry Dudley was killed in the battle by a cannonball—according to Robert, before his own eyes.[30]

Royal favourite

Robert Dudley was associated with Princess Elizabeth in 1557–1558,[31] and he was counted among her special friends by Philip II's envoy to the English court a week before Queen Mary's death.[20] On her accession Elizabeth immediately made him Master of the Horse, an important court position entailing close attendance on her. The post suited him, as he was an excellent horseman and showed great professional interest in royal transport and accommodation, horse breeding, and the supply of horses for all occasions. Dudley was also entrusted with organizing and overseeing a large part of the Queen's coronation festivities.[32]

In April 1559 Dudley was elected a Knight of the Garter in the good company of England's only duke and an earl, causing great wonder.[33] The ambassador of the neutral Republic of Venice, by his office the most detached of the foreign envoys,[34] soon wrote home: "My Lord Robert Dudley is ... very intimate with Her Majesty. On this subject I ought to report the opinion of many but I doubt whether my letters may not miscarry or be read, wherefore it is better to keep silence than to speak ill."[35] Philip II had already been informed shortly before Dudley's decoration:

Lord Robert has come so much into favour that he does whatever he likes with affairs and it is even said that her majesty visits him in his chamber day and night. People talk of this so freely that they go so far as to say that his wife has a malady in one of her breasts[note 1] and the Queen is only waiting for her to die to marry Lord Robert ... Matters have reached such a pass ... that ... it would ... be well to approach Lord Robert on your Majesty's behalf ... Your Majesty would do well to attract and confirm him in his friendship.[37]

Within a month, the Spanish ambassador, Count de Feria, counted Robert Dudley among those three persons who "rule everything".[note 2] Visiting foreigners of princely rank were bidding for his goodwill. He acted as official host on state occasions and was himself a frequent guest at ambassadorial dinners.[39] By the autumn of 1559 several foreign princes were vying for the Queen's hand;[40] their impatient envoys came under the impression that Elizabeth was fooling them, "keeping Lord Robert's enemies and the country engaged with words until this wicked deed of killing his wife is consummated."[41] "Lord Robert", the new Spanish ambassador, de Quadra, was convinced, was the man "in whom it is easy to recognize the king that is to be ... she will marry none but the favoured Robert."[42] Many of the nobility would not brook Dudley's new prominence, as they could not "put up with his being King."[43] Dudley's chief enemy at the time, the Duke of Norfolk,[44] threatened that Dudley "would not die in his bed",[45] and the Imperial envoy marvelled that he had "not been slain long ere this."[46] Plans to kill the favourite abounded;[47] one plot that remained a secret at the time was hatched by the Swedish ambassador.[48] Dudley took to wearing a light coat of mail under his clothes.[49] Among all classes, in England and abroad, gossip got under way that the Queen had children by Dudley—such rumours never quite ended for the rest of her life.[50]

Amy Dudley's death

Already in April 1559 court observers noted that Elizabeth never let Dudley from her side;[38] but her favour did not extend to his wife.[51] Lady Amy Dudley lived in different parts of the country since her ancestral manor house was uninhabitable.[52] Her husband visited her for four days at Easter 1559 and she spent a month around London in the early summer of the same year.[53] They never saw each other again; Dudley was with the Queen at Windsor Castle and possibly planning a visit to her, when his wife was found dead at her residence Cumnor Place near Oxford on 8 September 1560:[54]

there came to me Bowes, by whom I do understand that my wife is dead and as he sayeth by a fall from a pair of stairs. Little other understanding can I have of him. The greatness and the suddenness of the misfortune doth so perplex me, until I do hear from you how the matter standeth, or how this evil should light upon me, considering what the malicious world will bruit, as I can take no rest.[55]

Retiring to his house at Kew, away from court as from the putative crime scene, he pressed for an impartial inquiry which had already begun in the form of an inquest.[56] The jury found that it was an accident: Lady Dudley, staying alone "in a certain chamber", had fallen down the adjoining stairs, sustaining two head injuries and breaking her neck.[57] It was widely suspected that Dudley had arranged his wife's death to be able to marry the Queen. The scandal played into the hands of nobles and politicians who desperately tried to prevent Elizabeth from marrying him.[58] Some of these, like William Cecil and Nicholas Throckmorton, made use of it,[59] but did not themselves believe Dudley to be involved[60] in the tragedy which affected the rest of his life.[5]

Most historians have considered murder to be unlikely.[61] The coroner's report came to light in The National Archives in the late 2000s and is compatible with a fall as well as other violence.[62] In the absence of the forensic findings of 1560, it was often assumed that a simple accident could not be the explanation[63]—on the basis of near-contemporary tales that Amy Dudley was found at the bottom of a short flight of stairs with a broken neck, her headdress still standing undisturbed "upon her head",[64] a detail that first appeared as a satirical remark in the libel Leicester's Commonwealth of 1584 and has ever since been repeated for a fact.[65] To account for such oddities and evidence that she was ill, it was suggested in 1956 by Ian Aird, a professor of medicine, that Amy Dudley might have suffered from breast cancer, which through metastatic cancerous deposits in the spine, could have caused her neck to break under only limited strain, such as a short fall or even just coming down the stairs.[66] This explanation has been widely accepted.[67] Suicide has also often been considered an option, motives being Amy Dudley's depression or mortal illness.[68]

Marriage hopes and proposals

Elizabeth remained close with Dudley and he, with her blessing and on her prompting, pursued his suit for her hand in an atmosphere of diplomatic intrigue.[69] His wife's and his father's shadows haunted his prospects.[5] Pope Pius IV explained to one of his cardinals:

the greater part of the nobility of that island take ill the marriage which the said queen designs to enter with the Lord Robert Dudley ... they fear that if he becomes king, he will want to avenge the death of his father, and extirpate the nobility of that kingdom.[70]

Elizabeth countered such notions, saying that Lord Robert "was of a very good disposition and nature, not given by any means to seek revenge of former matters past".[70] His efforts leading nowhere, in the spring of 1561 Dudley offered to leave England to seek military adventures abroad; Elizabeth would have none of that and everything remained as it was.[5]

In October 1562 the Queen fell ill with smallpox and, believing her life to be in danger, she asked the Privy Council to make Robert Dudley Protector of the Realm and to give him a suitable title together with twenty thousand pounds a year. There was universal relief when she recovered her health; Dudley was made a privy councillor.[71] He was already deeply involved in foreign politics, including Scotland.[72] In 1563 Elizabeth suggested Dudley as a consort to the widowed Mary, Queen of Scots; this would be ideal to achieve firm amity between England and Scotland, diminishing the influence of foreign powers.[73] Her preferred solution was that they should all live together at the English court, so that she would not have to forgo her favourite's company.[5] The proposal was also to be a compensation for not marrying him herself, "whom, if it might lie in our power, we would make owner or heir of our own kingdom."[74] Mary of Scotland at first inquired if Elizabeth was serious, wanting above all to know her chances of inheriting the English crown.[75] Elizabeth let it be known, repeatedly, that she was only prepared to declare Mary her acknowledged heir on condition that she marry Robert Dudley, "and ... none else".[76] Mary's Protestant advisors warmed to the prospect of having Dudley as their prince,[77] and in September 1564 Elizabeth bestowed on him the earldom of Leicester, a move, in planning for years, which made him more acceptable to Mary.[78] Cecil hinted to the Scots that more was to follow.[79] In early 1565 Thomas Randolph, the English ambassador to Scotland, was told by the Scottish queen that she would accept the proposal.[80] To his amazement, Dudley was not to be moved to comply:

But a man of that nature I never found any ... he whom I go about to make as happy as ever was any, to put him in possession of a kingdom, to lay in his naked arms a most fair ... lady ... nothing regardeth the good that shall ensue unto him thereby ... but so uncertainly dealeth that I know not where to find him.[81]

Dudley indeed had made it clear to the Scots at the beginning that he was not a candidate for Mary's hand and forthwith had behaved with passive resistance.[82] He also worked in the interest of Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, Mary's eventual choice of husband.[83] Elizabeth herself had wavered as to declaring Mary her heir;[84] still, she finally told the Spanish ambassador that the proposal fell through because the Earl of Leicester refused to cooperate.[85]

By 1564 Dudley had realized that his chances of becoming Elizabeth's consort were small.[86] At the same time he could not "consider ... without great repugnance", as he said, that she chose another husband.[87] Confronted with other marriage projects, Elizabeth continued to say that she still would very much like to marry him.[88] Dudley was seen as a serious candidate until the mid-1560s and later.[89] To remove this threat to Habsburg and Valois suitors, between 1565 and 1578, four German and French princesses were mooted as brides for Leicester, as a consolation for giving up Elizabeth and his resistance to her foreign marriage projects.[90] These he had and would continue to sabotage.[91] In 1566 Dudley formed the opinion that Elizabeth would never marry, recalling that she had always said so since she was eight years old; but he still was hopeful—she had also assured him he would be her choice in case she changed her mind (and married an Englishman).[92] He was not alone in this assessment; the previous year, Philip II had written: "and after all, she will either not marry or else marry Robert, to whom she has always been so much attached ... the Queen is in love with Robert".[93]

Life at court

As "a male favourite to a virgin queen", Robert Dudley found himself in an unprecedented situation.[5] His apartments at court were next to Elizabeth's, in every residence.[94] Perceived by courtiers as knowing "the Queen and her nature best of any man", his influence was matched by few.[95] Another side of such privileges was Elizabeth's possessiveness and jealousy. His company was essential for her well-being and for many years he was hardly allowed to leave.[5] When the Earl was away for some weeks in 1578, Sir Christopher Hatton reported a growing emergency: "This court wanteth your presence. Her majesty is unaccompanied and, I assure you, the chambers are almost empty."[96]

Emotionally, Elizabeth's "surrogate husband",[5] Dudley was an unofficial consort on many ceremonial occasions, sometimes acting in the Queen's stead.[97] In a personal letter to the Earl of Shrewsbury, an old friend of Leicester's, Elizabeth said she considered Leicester as "another ourself".[98] Dudley largely assumed charge of court ceremonial and organized hundreds of small and large festivities,[99] being responsible for entertaining Elizabeth's guests.[100] Though he did not "delight in banquets", he had a peculiar taste for exotic fruits and salads—and French cooks.[101] From 1587 he was Lord Steward,[102] being responsible for the royal household's supply with food and other commodities. He displayed a strong sense for economizing and reform in this function, which he had de facto occupied long before his official appointment.[103] The sanitary situation in the palaces was a perennial problem and a talk with Leicester about these issues inspired John Harington to construct a water closet.[101] Leicester was a lifelong sportsman, hunting and jousting in the tiltyard.[101] He was also the Queen's regular dancing partner[104] and an indefatigable tennis-player;[101] sometimes Elizabeth watched: One morning in 1565 Dudley "took the Queen's napkin out of her hand and wiped his face".[105] His tennis-partner, the Duke of Norfolk, was outraged, swearing Leicester "was too saucy, and ... that he would lay his racket upon his face";[105] Elizabeth was angry with the Duke and armed followers of Norfolk and Leicester, wearing their respective colours, soon patrolled the court.[106]

Ancestral and territorial ambition

After the Duke of Northumberland's attainder the entire Dudley inheritance had disappeared. His sons had to start from scratch in rebuilding the family fortunes, as they had renounced any rights to their father's former possessions or titles when their own attainder had been lifted in 1558.[108] In the first years of the new reign Dudley's financial situation was very precarious and he could only finance the lifestyle expected of a royal favourite by large loans from City of London merchants. With time Elizabeth's material generosity towards Dudley proved singular, his most important sources of income deriving from monopolies and export licences.[101] In 1563, in anticipation of his peerage,[109] the Queen granted Dudley Kenilworth Manor, Castle, and Park, a large Warwickshire possession of the Crown, together with the lordships of Denbigh and Chirk in North Wales. Other grants were to follow.[110] All in all, Leicester and his elder brother, Ambrose, Earl of Warwick, came to preside over the greatest aristocratic interest in the West Midlands and North Wales.[111]

Warwick and Kenilworth

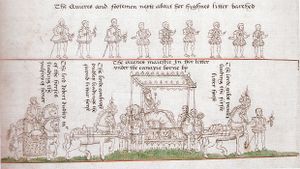

Ambrose and Robert Dudley were very close, in matters of business and personally.[112] Through their paternal grandmother, they descended from the Hundred Years War heroes, John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, and Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick.[113] Robert Dudley was especially fascinated by the Beauchamp descent and, with his brother, adopted the ancient heraldic device of the earls of Warwick, the bear and ragged staff.[114] Due to such genealogical aspects the West Midlands held a special significance for him.[115] He went to great lengths and spent absurd sums to acquire specific lands in his attempt to rebuild and perpetuate the House of Dudley.[116] The town of Warwick felt this during a magnificent visit by the Earl in 1571, for a celebration of the feast of the order of Saint Michael. With the latter Dudley had been invested by the French king in 1566. "Aparelled all in white ... the proportions and lineaments of his body" made such an impression that he was accounted "the goodliest [best looking] male personage in England" by the onlookers.[117] By these festivities Leicester celebrated himself as the heir of the Beauchamps. Lord Leycester's Hospital, a charity for aged and injured soldiers still functioning today, he founded shortly afterwards in the same spirit.[118]

Kenilworth Castle was the centre of Leicester's ambitions to "plant" himself in the region.[119] He holidayed at the castle almost every year from 1570.[120] In July 1575 he staged a final allegorical bid for the Queen's hand in the form of a nineteen-day-festival. There were a Lady of the Lake, a swimming papier-mâché dolphin with a little orchestra in its belly, fireworks, masques, hunts, and popular entertainments like bear baiting.[121] The whole scenery of landscape, artificial lake, castle, and renaissance garden was ingeniously used for the entertainment.[122] When Elizabeth arrived, time stood literally still, as the great tower clock of the castle was stopped for the time of her visit.[123]

Denbighshire

When Robert Dudley entered his new Welsh possessions in 1563 there had existed a tenurial chaos for more than half a century. Some leading local families benefited from this to the detriment of the Crown's revenue. To remedy this situation, and to increase his own revenue, Dudley effected compositions with the tenants.[124] In exchange for newly agreed rents all tenants that had so far only been copyholders were raised to the status of freeholders at one stroke. Additionally, all tenants' rights of common were secured as were the boundaries of the commons, striking a balance between property rights and protection against enclosure.[125] Simon Adams, who has researched Dudley's Welsh connections in depth,[126] concludes: "the tenurial reformation he undertook in the lordships of Denbigh and Chirk reveals an administrative ability that has often been overlooked. This was an ambitious resolution of a long-standing problem ... without parallel in Elizabeth's reign."[120]

Though an absentee landlord, Leicester regarded Denbighshire as an integral part of a territorial base for a revived House of Dudley.[127] He checked the domination of the county by the Salusbury family—a situation which pleased other families[128]—and set about developing the town of Denbigh with large building projects;[129] the church he planned, though, was never finished, being too ambitious. It would not only have been the largest,[130] but also the first post-Reformation church in England and Wales built according to a plan where the preacher was to take the centre instead of the altar, thus stressing the importance of preaching in the Protestant Church. In vain Leicester tried to have the nearby episcopal see of St. Asaph transferred to Denbigh.[131] He also encouraged and supported the translation of the Bible and the Common Prayer Book into Welsh.[132]

Love affairs and remarriage

Confronted by a Puritan friend with rumours about his "ungodly life",[133] Dudley defended himself in 1576:

I stand on the top of the hill, where ... the smallest slip seemeth a fall ... I may fall many ways and have more witnesses thereof than many others who perhaps be no saints neither ... for my faults ... they lie before Him who I have no doubt but will cancel them as I have been and shall be most heartily sorry for them.[134]

With Lady Douglas Sheffield, a young widow of the Howard family, he had a serious relationship from the late 1560s.[135] He explained to her that he could not marry, not even in order to beget a Dudley heir, without his "utter overthrow":[136]

You must think it is some marvellous cause ... that forceth me thus to be cause almost of the ruin of mine own house ... my brother you see long married and not like to have children, it resteth so now in myself; and yet such occasions is there ... as if I should marry I am sure never to have [the Queen's] favour".[137]

Although in this letter Leicester said he still loved her as he did at the beginning, he offered her his help to find another husband for reasons of respectability if she so wished.[138] The affair continued and in 1574 Lady Douglas gave birth to a son, also called Robert Dudley.[139]

Lettice Knollys was the wife of Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex and first cousin once removed of Queen Elizabeth on her mother's side.[140] Leicester had flirted with her in the summer of 1565, causing a prolonged outbreak of jealousy in the Queen.[141] After Lord Essex went to Ireland in 1573, they possibly became lovers.[142] There was much talk, and on Essex' return in December 1575, "great enmity between the Earl of Leicester and the Earl of Essex" was expected.[143] Leicester was in support of sending Essex back to Ireland,[144] where he died soon of dysentery. Rumours of poison, administered by the Earl of Leicester's means, were soon abroad. An official investigation conducted by Henry Sidney, Lord Deputy of Ireland and Leicester's brother-in-law, did not find any indications of foul play but "a disease appropriate to this country ... whereof ... died many".[145] The rumours continued.[146]

The prospect of marriage to the Countess of Essex on the horizon, Leicester finally drew a line under his relationship with Lady Douglas Sheffield and, other than she later claimed, they came to a friendly agreement over their son's custody.[5] Young Robert grew up in Dudley's and his friends' houses, but had "leave to see" his mother until she left England in 1583.[147] Leicester was very fond of his son and gave him an excellent education.[148] He willed him to inherit the bulk of his estate after his brother Ambrose's death, including Kenilworth Castle.[149] Douglas Sheffield remarried in 1579. After the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, the younger Robert Dudley tried unsuccessfully to prove that his parents had married thirty years earlier in a secret ceremony. In that case he would have been able to claim the earldoms of Leicester and Warwick.[150] His mother supported him, but maintained that she had been strongly against raising the issue and was possibly pressured by her son.[151] Leicester himself had throughout considered the boy as illegitimate.[152][note 3]

On 21 September 1578 Leicester secretly married Lady Essex at his country house at Wanstead, with only a handful of relatives and friends present.[159] He did not dare to tell the Queen of his marriage; nine months later Leicester's enemies at court acquainted her with the situation, causing a furious outburst.[160] She already had been aware of his marriage plans a year earlier, though.[161] Leicester's hope of an heir was fulfilled in 1581 when another Robert Dudley, styled Lord Denbigh, was born.[162] The child died aged three in 1584, leaving behind disconsolate parents.[163] Leicester found comfort in God since, as he wrote, "princes ... seldom do pity according to the rules of charity."[164] The Earl turned out to be a devoted husband:[165] In 1583 the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau, wrote of "the Earl of Leicester and his lady to whom he is much attached", and "who has much influence over him".[166] To all his four stepchildren Leicester was a concerned parent.[167] In every respect he worked for the advancement of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, whom he regarded as his political heir.[168]

The marriage of her favourite hurt the Queen deeply. She never accepted it,[169] humiliating Leicester in public: "my open and great disgraces delivered from her Majesty's mouth".[170] Then again, she would be as fond of him as ever.[171] In 1583 she informed ambassadors that Lettice Dudley was "a she-wolf" and her husband a "traitor" and "a cuckold".[172] Lady Leicester's social life was much curtailed.[173] Even her movements could pose a political problem, as Francis Walsingham explained: "I see not her Majesty disposed to use the services of my Lord of Leicester. There is great offence taken at the conveying down of his lady."[174] The Earl stood by his wife, asking his colleagues to intercede for her; there was no hope:[175] "She [the Queen] doth take every occasion by my marriage to withdraw any good from me", Leicester wrote still after seven years of marriage.[176]

Colleagues and politics

As a privy councillor Robert Dudley was one of the most frequently attending and heavily involved in day-to-day business.[177] In 1578 the Spanish ambassador Bernardino de Mendoza described Elizabeth's government: "although there are seventeen councillors ... the bulk of the business really depends upon the Queen, Leicester, Walsingham and Cecil".[178] The last three have been called "the triumvirate" by Alan Haynes;[179] while, for the first thirty years of the reign, Simon Adams sees William Cecil and Robert Dudley as "the most important councillors", working intimately with the Queen.[180]

In 1560 the diplomat Nicholas Throckmorton advocated vehemently against Dudley marrying the Queen, but Dudley won him over in 1562.[181] Throckmorton henceforth became his political advisor and intimate. After Throckmorton's death in 1571 there quickly evolved a political alliance between the Earl of Leicester and Sir Francis Walsingham, soon to be Secretary of State. Together they worked for a militant Protestant foreign policy.[182] There also existed a family relationship between them after Walsingham's daughter had married Philip Sidney, Leicester's favourite nephew.[183] Leicester, after some initial jealousy on his part, also became a good friend of Sir Christopher Hatton, himself one of Elizabeth's favourites.[184]

Robert Dudley's relationship with William Cecil, Lord Burghley was complicated. Traditionally they have been seen as enemies, and Cecil behind the scenes sabotaged Dudley's endeavours to obtain the Queen's hand.[185] On the other hand they were on friendly terms and had an efficient working relationship which never broke down.[186] On the whole, Cecil and Dudley were in concord about policies while disagreeing fundamentally about some issues, such as the Queen's marriage and some areas of foreign policy.[187] Cecil favoured the suit of Francois, Duke of Anjou in 1578–1581 for Elizabeth's hand, while Leicester was among its strongest opponents,[91] even contemplating exile in letters to Burghley.[188] The Anjou courtship, at the end of which Leicester and several dozen noblemen and gentlemen escorted the French prince in triumph to Antwerp,[189] also touched the question of English intervention in the Netherlands to help the rebellious provinces. This debate stretched over a decade until 1585, with the Earl of Leicester as the foremost interventionist. Burghley was more cautious of military engagement while in a dilemma over his Protestant predilections.[190] In 1572 the vacant post of Lord High Treasurer was offered to Leicester; he declined and proposed Burghley, stating that the latter was the much more suitable candidate.[191] In later years, being at odds, Dudley felt like reminding Cecil of their "thirty years friendship".[192]

Turning against Mary Stuart

Until about 1571/1572 Dudley supported Mary Stuart's succession rights to the English throne.[194] He was also, from the early 1560s, on the best terms with the Protestant lords in Scotland, thereby supporting the English or, as he saw it, the Protestant interest.[195] After Mary Stuart's flight into England (1568) Leicester was, unlike Cecil,[196] in favour of restoring her as Scottish queen under English control, preferably with a Protestant English husband—as long as he himself would not be the intended bridegroom (which had been suggested).[197] "For there is danger from delivering of her to her Government, so is there danger in retaining her in prison",[198] he wrote in 1571. Shortly after the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre in 1572 Cecil, Leicester, and Elizabeth engaged in a top-secret plan to extradite Mary to the Scottish regency government, who would then immediately execute her. The scheme failed due to the unexpected death of the Scottish regent.[199] In 1577 Leicester had a courteous meeting with Mary, lending a sympathetic ear to her complaints of captivity.[200] As Mary might be their future sovereign, Elizabeth's ministers had cause to show their goodwill towards the captive Queen now and then;[201] Leicester's was at an end in 1584. He was stung by the publication of the Catholic anti-Leicester libel, Leicester's Commonwealth, believing that Mary was involved in its conception. "Leicester has lately told a friend that he will persecute you to the uttermost", she was informed.[202]

Dudley was probably behind the Bond of Association, which the Privy Council gave out in October 1584. Being circulated in the country, the subscribers swore that, should Elizabeth be assassinated (as William the Silent had been a few months earlier), not only the killer but also the royal person who would benefit from this should be executed.[203] In 1586 Walsingham uncovered the Babington Plot; after the Ridolfi Plot (1571), and the Throckmorton Plot (1583), this was a further scheme to assassinate Elizabeth in which Mary was involved. Following her conviction, Leicester, then in the Netherlands, vehemently urged her execution in his letters; he despaired of Elizabeth's security after so many plots.[204] Back in England, he met James VI's delegate in his coach. The Scot had been sent to demand that Mary's life be spared.[205] After having bluntly emphasized how desirable Mary's death would be to James, Leicester was left with the impression that the King would not try to avenge his mother's execution, his succession to the English Crown provided. King James' own tacit, but important, approval followed between the lines in a sophisticated letter to the Earl.[206]

In February 1587 Elizabeth signed Mary's death warrant with the proviso that it be not carried out until she gave green light. As there was no sign of her doing so, some members of the Privy Council decided to proceed with Mary's execution in the interest of the state, against Elizabeth's wishes. They were, among others, Burghley and Leicester, but not Walsingham who was ill. The Queen's anger at the news of Mary's death was terrifying. Despite all pleadings Burghley was not allowed into the royal presence for several months.[207] Leicester went to Bath and Bristol for his health;[208] unlike the other culprits and to Burghley's dismay, he escaped Elizabeth's personal wrath entirely.[209]

Patronage

Exploration and business

Robert Dudley was a pioneer of new industries; interested in many things from tapestries to mining, he was engaged in the first joint stock companies in English history.[211] The Earl also concerned himself with relieving unemployment among the poor.[212] On a personal level, he gave to poor people, petitioners, and prisons on a daily basis.[101] Due to his interests in trade and exploration, as well as his debts, his contacts with the London city fathers were intense.[101] He was an enthusiastic investor in the Muscovy Company and the Merchant Adventurers.[213] English relations with Morocco were also handled by Leicester. This he did in the manner of his private business affairs, underpinned by a patriotic and missionary zeal (commercially, these relations were a losing business).[214] Much interest he took in the careers of John Hawkins and Francis Drake, from early on, and he was a principal backer of Drake's circumnavigation of the world. Robert and Ambrose Dudley were also principal patrons of Martin Frobisher's 1576 search for the Northwest Passage.[215] Later Leicester acquired his own ship, the Galleon Leicester, which he employed in a luckless expedition under Edward Fenton, but also under Drake. As much as profit, English seapower was on his mind and accordingly, Leicester became a friend and leading supporter of Dom António, the exiled claimant to the Portuguese throne after 1580.[216]

Learning, theatre, the arts, and literature

Apart from their legal function the Inns of Court were the Tudor equivalents of gentlemen's clubs.[217] In 1561, grateful for favours he had done them, the Inner Temple admitted Dudley as their most privileged member, their "Lord and Governor".[218] He was allowed to build his own apartments on the premises and organized grand festivities and performances in the Temple.[219] As Chancellor of Oxford University Dudley was highly committed,[220] if somewhat authoritarian. He frowned upon the dangerous play of football and the extravagant clothing of students.[221] Leicester enforced the Thirty-nine Articles and the oath of royal supremacy at Oxford, and obtained from the Queen an incorporation by Act of Parliament for the university.[222] He was also instrumental in refounding Oxford University Press.[223] He installed the pioneer of international law, Alberico Gentili, and the exotic theologian, Antonio del Corro, at Oxford; over del Corro's controversial case, Leicester even sacked the university's Vice-Chancellor.[224]

Robert Dudley was a history enthusiast,[225] and in 1559 he suggested to the tailor John Stow to become a chronicler (as Stow recalled in 1604).[226] The other chroniclers, Richard Grafton and Raphael Holinshed, enjoyed his patronage as well.[227] Robert Dudley's personal company of players is traceable from 1559, and in 1574 he obtained for them the first royal patent that was ever issued to actors so that they could tour the country unmolested by local authorities. The head of Leicester's Men was James Burbage, a former joiner, who around 1577 erected the first permanent English theatre building, called: The Theatre.[228] The Earl also kept a separate company of musicians who in 1586 played before the King of Denmark; with them travelled William Kempe, "the Lord Leicester's jesting player".[229]

Leicester possessed one of the largest and finest collections of paintings in Elizabethan England, being the first great private collector.[231] He was a principal patron of Nicholas Hilliard,[232] and a garden design enthusiast, interested in all aspects of Italian culture.[233] The Earl's circle of scholars and literary men included, among others, his nephew Philip Sidney, the astrologer and Hermeticist John Dee, his secretaries Edward Dyer and Jean Hotman, as well as John Florio and Gabriel Harvey.[234] Through Harvey, Edmund Spenser found employment at Leicester House on the Strand, the Earl's palatial town house; there he wrote his first works of poetry.[235] Many years after Leicester's death Spenser wistfully recalled this time in his Prothalamion,[236] and in 1591 he remembered the late Earl with his poem The Ruins of Time.[237]

Religion

From infancy Robert Dudley grew up as a Protestant.[5] Under Mary I he conformed in the same way as his old tutor, Roger Ascham, or Princess Elizabeth.[238] During the early years of Elizabeth's reign he was a major patron to returning Puritan exiles and supported the French Huguenots.[5] He also had Catholic contacts, yet by the mid-1560s was exclusively identified with advanced Protestantism.[239] In 1568 the French ambassador described him as "totally of the Calvinist religion".[240] After the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre in 1572 this trait in him became the more pronounced, and he continued as the chief patron of English Puritans and a champion of international Calvinism.[241]

Dudley went to great lengths to support non-conforming preachers, while warning them against too radical positions which, he argued, would only endanger what reforms had been hitherto achieved.[242] He would not condone the overthrow of the existing church model because of "trifles",[243] he said: "I am not, I thank God, fantastically persuaded in religion but ... do find it soundly and godly set forth in this universal Church of England."[244] Accordingly, he tried to smooth things out and, among other moves, initiated several disputations between the more radical elements of the church and the episcopal side so that they "might make reconcilement".[245] His influence in ecclesiastical matters was considerable until it declined in the 1580s under Archbishop John Whitgift.[246] Dudley was instrumental in preferring at least six of the earliest Elizabethan bishops to their sees; among them Edmund Grindal, Edwin Sandys and Thomas Young.[247] All these bishops felt themselves obliged to him.[248] Many of the highest clergy had been and considered themselves as his servants. The Earl expected them to follow his orders and, in 1578, he scolded Bishop Edmund Scambler and his colleagues for forgetting formerly held ideals: "The care of this world truly hath choked you all, yea almost all".[249]

Leicester was especially interested in the furtherance of preaching, which was the main concern of moderate Puritanism.[250] He backed this brand of Puritanism in counties where he had influence and habitually appeared at public preaching exercises when travelling in the country.[251] On the other hand, in his household, Leicester employed Catholics like Sir Christopher Blount, who held a position of trust and of whom he was personally fond. The Earl's patronage of and reliance on individuals was as much a matter of old family loyalties or personal relationships as of religious allegiances.[252] Such ties explain Leicester's concern for Edmund Campion,[253] who had been the Earl's protégé at Oxford University and in his service for a time, before he went abroad to become a Jesuit.[254] After his arrest in 1581 he was imprisoned in the Tower of London in a tiny cell where he could neither stand nor lie down. Leicester and the Earl of Bedford examined him in Leicester House, offering him his life and liberty if he returned to the Protestant faith. Campion would not do that. A contemporary Italian account reports: "The Earls greatly admired his virtue and learning ... and said it was a pity he was a papist ... They ordered his heavy irons to be removed and that [he be given] a bed and other necessaries".[253]

Governor-General of the United Provinces

During the 1570s Leicester built a special relationship with Prince William of Orange, who held him in high esteem. The Earl became generally popular in the Netherlands. Since 1577 he pressed for an English military expedition, led by himself (as the Dutch strongly wished) to succour the rebels.[255] In 1584 the Prince of Orange was murdered, political chaos ensued, and in July 1585 Antwerp fell to the Duke of Parma.[256] An English intervention was inevitable. It was decided that Leicester would go to the Netherlands and "be their chief as heretofore was treated of", as he phrased it in August 1585.[257] He was alluding to the recently signed Treaty of Nonsuch in which his position and authority as "governor-general" of the Netherlands had only been vaguely defined.[258]

At the end of December 1585 Leicester was received in the Netherlands, according to one correspondent, in the manner of a second Charles V; a Dutch town official already noted in his minute-book that the Earl was going to have "absolute power and authority".[259] After a progress through several cities and so many festivals he arrived in The Hague, where on 1 January 1586 he was urged to accept the title governor-general by the States General of the United Provinces. Leicester wrote to Burghley and Walsingham, explaining why he believed the Dutch importunities should be answered favourably. He accepted his elevation on 25 January, having not yet received any communications from England due to constant adverse winds.[260]

The Earl had now "the rule and government general" with a Council of State to support him (the members of which he nominated himself).[261] He remained a subject of Elizabeth, making it possible to contend that she was now sovereign over the Netherlands. According to Leicester, this was what the Dutch desired.[262] From the start such a position for him had been implied in the Dutch propositions to the English, and in their instructions to Leicester; and it was consistent with the Dutch understanding of the Treaty of Nonsuch.[263] The English queen, however, in her instructions to Leicester, had expressly declined to accept offers of sovereignty from the United Provinces while still demanding of the States to follow the "advice" of her lieutenant-general in matters of government.[264] Her ministers on both sides of the Channel hoped she would accept the situation as a fait accompli and could even be persuaded to add the rebellious provinces to her possessions.[265] Instead her fury knew no bounds and Elizabeth sent Sir Thomas Heneage to read out her letters of disapproval before the States General, Leicester having to stand nearby.[266] Elizabeth's "commandment"[267] was that the Governor-General immediately resign his post in a formal ceremony in the same place where he had taken it.[266] After much pleading with her and protestations by the Dutch, it was postulated that the governor-generalship had been bestowed not by any sovereign, but by the States General and thereby by the people.[268] The damage was done, however:[269] "My credit hath been cracked ever since her Majesty sent Sir Thomas Heneage hither", Leicester recapitulated in October 1586.[270]

Elizabeth demanded of her Lieutenant-General to refrain at all cost from any decisive action with Parma, which was the opposite of what Leicester wished and what the Dutch expected of him.[271] After some initial successes,[272] the unexpected surrender of the strategically important town of Grave was a serious blow to English morale. Leicester's fury turned on the town's governor, Baron Hemart, whom he had executed despite all pleadings. The Dutch nobility were astonished: even the Prince of Orange would not have dared such an outrage, Leicester was warned; but, he wrote, he would not be intimidated by the fact that Hemart "was of a good house".[273]

Leicester's forces, heavily underfinanced and small, faced the most formidable army in Europe.[274] Their unity was at risk by Leicester's and the other commanders' quarrels with Sir John Norris, the Earl's deputy and himself a difficult character.[275] Elizabeth for many months delayed sending promised funds and troops, much aggravating the soldiers' lot.[276] "They cannot get a penny; their credit is spent; they perish for want of victuals and clothing in great numbers ... I assure you it will fret me to death ere long to see my soldiers in this case and cannot help them",[277] Leicester wrote home. Four months later, mass desertions occurring, he commented: "I do but wonder to see they do not rather kill us all than run away, God help us!"[278]

Many Dutch statesmen were essentially politiques; they soon became disenchanted with the Earl's enthusiastic fostering of what he called "the religion".[279] His most loyal friends were the Calvinists at Utrecht and Friesland, provinces in constant opposition to Holland and Zeeland.[280] Those rich provinces engaged in a lucrative trade with Spain which was very helpful to either side's war effort. Encouraged by the poorer sections of Dutch society, Leicester enforced a ban on this trade with the enemy, thus alienating the wealthy Dutch merchants. He also effected a fiscal reform. In order to centralize finances and to replace the highly corrupt tax farming with direct taxation, a new Council of Finances was established which was not under supervision of the Council of State. The Dutch members of the Council of State were outraged at these bold steps.[281] English peace talks with Spain behind Leicester's back, which had started within days after he had left England, undermined his position further.[282]

In September 1586 there was a skirmish at Zutphen, in which Philip Sidney was wounded. He died a few weeks later. His uncle's grief was great.[283] In December Leicester returned to England. In his absence, William Stanley and Rowland York, two Catholic officers whom Leicester had placed in command of Deventer and the fort of Zutphen, respectively, went over to Parma, along with their key fortresses—a disaster for the Anglo-Dutch coalition in every respect.[284] His Dutch friends, as his English critics, pressed for Leicester's return to the Netherlands. Shortly after his arrival in June 1587 the English-held port of Sluis was lost to Parma, Leicester being unable to assert his authority over the Dutch allies, who refused to cooperate in relieving the town.[285] After this blow Elizabeth, who ascribed it to "the malice or other foul error of the States",[286] was happy to enter into peace negotiations with the Duke of Parma. By December 1587 the differences between Elizabeth and the Dutch politicians, with Leicester in between, had become insurmountable; he asked to be recalled by the Queen and gave up his post.[287] He was irredeemably in debt because of his personal financing of the war.[288]

.jpg)

Armada and death

In July 1588, as the Spanish Armada came nearer, the Earl of Leicester was appointed "Lieutenant and Captain-General of the Queen's Armies and Companies".[290] At Tilbury on the Thames he erected a camp for the defence of London, should the Spaniards indeed land. Leicester vigorously counteracted the disorganization he found everywhere, having few illusions about "all sudden hurley-burleys", as he wrote to Walsingham.[291] When the Privy Council was already considering to disband the camp to save money, Leicester held against it, setting about to plan with the Queen a visit to her troops. On the day she gave her famous speech he walked beside her horse bare-headed.[292]

After the Armada the Earl was seen riding in splendour through London "as if he were a king".[293] For the past weeks he had usually dined with the Queen, a unique favour.[293] On his way to Buxton in Derbyshire to take the baths, he died at Cornbury Park near Oxford on 4 September 1588. A man named Smith claimed to have bewitched the Earl into eternity; the Privy Council decided on malaria and let Smith go free.[294] The Earl's health had not been good for some time, and as causes of death historians have considered malaria,[101] but also stomach cancer or a heart condition.[295] Only a week earlier Leicester had said farewell to his Queen. Elizabeth was deeply affected and locked herself in her apartment for a few days until Lord Burghley had the door broken.[296] Her nickname for Dudley was "Eyes", which was symbolized by the sign of ôô in their letters to each other.[297] Elizabeth kept the letter he had sent her six days before his death in her bedside treasure box, endorsing it with "his last letter" on the outside. It was still there when she died fifteen years later.[298]

Leicester was buried, as he had requested, in the Beauchamp Chapel in Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick—in the same chapel as Richard Beauchamp, his ancestor, and the "noble Impe", his little son.[299] Countess Lettice was also buried there when she died in 1634, alongside the "best and dearest of husbands", as the epitaph, which she commissioned, says.[300]

Historiographical treatment

The book which later became known as Leicester's Commonwealth was written by Catholic exiles in Paris and printed anonymously in 1584.[301][note 4] It was published shortly after the death of Leicester's son, which is alluded to in a stop-press marginal note: "The children of adulterers shall be consumed, and the seed of a wicked bed shall be rooted out."[304] Smuggled into England, the libel became a bestseller with underground booksellers and the next year was translated into French.[305] Its underlying political agenda is the succession of Mary Queen of Scots to the English throne,[306] but its most outstanding feature is an allround attack on the Earl of Leicester. He is portrayed as an atheistic, hypocritical coward, a "perpetuall Dictator",[307] terrorizing the Queen and ruining the whole country. He is engaged in a long-term conspiracy to snatch the Crown from Elizabeth and to settle it on himself. Spicy details of his monstrous private life are revealed, and he appears as an expert poisoner of innumerable high-profile personalities.[308] This influential classic is the origin of many aspects of Leicester's historical reputation.[309]

In the 1590s Leicester was the "honour of England"[310] and "Earl of Excellence" to the lexicographer John Florio.[311] At the same time he was about to become the most accomplished intriguer at court—and a model for manipulating the Queen.[3] This theme was developed by William Camden, who established Robert Dudley as the perfect courtier with an all-pervading sinister influence.[312] Some of the most often-quoted characterizations of Leicester, such as that he "was wont to put up all his passions in his pocket", his nickname of "the Gypsy", and Elizabeth's "I will have here but one mistress and no master"-reprimand to him, were contributed by Sir Henry Wotton and Sir Robert Naunton almost half a century after the Earl's death.[313] James Anthony Froude, the Victorian, saw Robert Dudley as Elizabeth's soft plaything, combining "in himself the worst qualities of both sexes. Without courage, without talent, without virtue".[314] The habit of comparing him unfavourably to William Cecil[315] was continued by Conyers Read in 1925: "Leicester was a selfish, unscrupulous courtier and Burghley a wise and patriotic statesman".[316] Geoffrey Elton, in his widely-read England under the Tudors (1955), saw Dudley as "a handsome, vigorous man with very little sense."[317]

Since the 1950s academic assessment of the Earl of Leicester has undergone considerable changes.[318] Leicester's importance in literary patronage was established by Eleanor Rosenberg in 1955. Since the 1960s Elizabethan Puritanism has been thoroughly reassessed and Patrick Collinson has outlined the Earl's place in it.[318] Dudley's religion could thus be better understood, rather than simply to brand him as a hypocrite.[319] Leicester's importance as a privy councillor and statesman has often been overlooked;[97] one reason being that many of his letters are scattered among private collections and not easily accessible in print, as are those of his colleagues Walsingham and Cecil.[5] Alan Haynes describes him as "one of the most strangely underrated of Elizabeth's circle of close advisers",[320] while Simon Adams, who since the early 1970s has researched many aspects of Leicester's life and career,[321] concludes: "Leicester was as central a figure to the 'first reign' [of Elizabeth] as Burghley."[322]

See also

- Alienation Office

- Cultural depictions of Elizabeth I of England

- Greenwich armour

- Kenilworth (novel)

- Lady Catherine Grey

- Maria Stuarda

- Mary Stuart (play)

Footnotes

- ↑ "está muy mala de un pecho" ("she is very ill in one breast"), in the original Spanish.[36]

- ↑ The others were William Cecil and his brother-in-law Nicholas Bacon.[38]

- ↑ Sir Robert Dudley lost his case in the Star Chamber in 1605.[153] Historians have had different views on the problem, for example: Derek Wilson believes in a marriage;[154] G.F. Warner was very sceptical of it;[155] it has been rejected by Conyers Read,[156] Johanna Rickman,[157] and Simon Adams.[158]

- ↑ The original title began: The copie of a leter, wryten by a Master of Arte of Cambrige ....[302] In 1641 it was reprinted in London as Leycesters Commonwealth.[303]

Citations

- ↑ Haynes 1992 p. 12; Wilson pp. 151–152

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 145, 147

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Adams 2002 p. 52

- ↑ Loades 1996 p. 225

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Adams 2008c

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 133

- ↑ Wilson p. 16

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 55–56

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 55

- ↑ Wilson pp. 23, 28–29

- ↑ Jenkins p. 300; Adams 1996

- ↑ Wilson pp. 31, 33, 44

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 135, 159

- ↑ Loades 1996 pp. 179, 225, 285; Haynes 1987 pp. 20–21

- ↑ Loades 1996 pp. 225–226; Wilson pp. 45–47

- ↑ Loades 1996 pp. 256–257, 238–239

- ↑ Ives pp. 199, 209; Haynes 1987 pp. 23

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 23–24; Chamberlin p. 68, 69

- ↑ Loades 1996 pp. 266, 270–271

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Adams 2002 p. 134

- ↑ Wilson p. 66

- ↑ Nichols p. 33

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 157, 134

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 83; Adams 2002 p. 158

- ↑ Loades 1996 p. 280

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 161–162

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 85; Loades 1996 pp. 273, 280

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 158; Wilson p. 71; Chamberlin pp. 85–86

- ↑ Loades 1996 p. 273

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 134; Chamberlin pp. 87–88

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 381; Adams 1996

- ↑ Wilson pp. 78, 83–92

- ↑ Wilson p. 96

- ↑ Ives p. 26

- ↑ Gristwood p. 125

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 63

- ↑ Hume 1892–1899 Vol. I pp. 57–58; Wilson p. 95

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Chamberlin p. 101

- ↑ Owen p. 9

- ↑ Skidmore p. 162

- ↑ Skidmore p. 166; Gristwood p. 129

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 118

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 116–117; Doran p. 42

- ↑ Loades 1996 p. 283

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 116

- ↑ Gristwood p. 129

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 78; Wilson p. 100; Chamberlin p. 117

- ↑ Loades 2004 p. 269

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 151

- ↑ Wilson p. 114; Doran p. 72

- ↑ Adams 2008a

- ↑ Adams 1995 pp. 380–382

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 378

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 383

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 136

- ↑ Doran p. 43; Skidmore p. 382

- ↑ Skidmore p. 378

- ↑ Owen p. 10; Doran p. 45

- ↑ Haigh p. 16; Wilson pp. 115–116, 125, 127–128; Gristwood pp. 144–145

- ↑ Historical Manuscripts Commission p. viii; Gristwood p. 149

- ↑ Wilson p. 124; Doran p. 44

- ↑ Skidmore pp. 230–233

- ↑ Doran pp. 42–44

- ↑ Jenkins p. 65

- ↑ Jenkins p. 291

- ↑ Jenkins p. 65; Gristwood pp. 155–156

- ↑ Doran p. 44

- ↑ Gristwood pp. 153, 160–163; Doran p. 44

- ↑ Doran p. 45–52; Adams 2008c

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Adams 2002 p. 165

- ↑ Wilson p. 136

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 137

- ↑ Wilson pp. 140–141

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 145; Wilson p. 240

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 138–139

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 136, 160, 144–145

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 140, 146, 147

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 321, 358

- ↑ Wilson p. 142

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 151–152

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 158

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 143–144, 152, 158, 168; Wilson p. 141; Jenkins p. 119

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 152; Wilson p. 142

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 155, 156–157, 159–161

- ↑ Fraser p. 267; Wilson p. 243

- ↑ Doran p. 65

- ↑ Hume 1904 p. 90; Doran p. 65

- ↑ Hume 1904 pp. 90–94, 99, 101–104; Jenkins p. 130

- ↑ Doran p. 212

- ↑ Hume 1904 pp. 94, 95, 138, 197; Doran p. 124

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Doran pp. 212–213

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 139

- ↑ Haynes 1987 p. 47

- ↑ Gristwood p. 198; Girouard 1979 p. 111

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 140; Wilson p. 305

- ↑ Wilson p. 230

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Wilson p. 305

- ↑ Lovell pp. 265–267; 355

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 120; Wilson pp. 78, 305

- ↑ Martyn p. 40

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 101.3 101.4 101.5 101.6 101.7 Adams 1996

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 43

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 141–144; Wilson pp. 326–327

- ↑ Loades 2004 p. 271

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Williams p. 91

- ↑ Wilson pp. 176–177

- ↑ Girouard 2009 p. 445

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 319

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 321

- ↑ Haynes 1987 p. 59; Adams 2002 p. 235

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 310; Wilson p. 170

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 322, 3

- ↑ Wilson pp. 1, 3

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 312–313, 321

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 312–313, 320–321, 326

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 320–321, 322–323, 384, 200–201

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 179–181

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 327

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 312

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Adams 2002 p. 3

- ↑ Doran pp. 67–69; Jenkins pp. 205–211

- ↑ Henderson pp. 90–92

- ↑ Jenkins p. 207

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 264, 272, 275, 325, 361

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 268–269, 275–276

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 2

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 3, 275–276

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 386, 302–306

- ↑ Wilson pp. 171–172

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 225

- ↑ Wilson p. 172; Adams 2002 p. 225

- ↑ Wilson p. 173

- ↑ Gristwood p. 322

- ↑ Gristwood pp. 322–323

- ↑ Rickman p. 49

- ↑ Read p. 24

- ↑ Read p. 25

- ↑ Read pp. 23, 26

- ↑ Warner pp. iii–iv

- ↑ Jenkins p. 124

- ↑ Hume 1892–1899 Vol. I p. 472; Jenkins pp. 124–125

- ↑ Adams 2008b

- ↑ Jenkins p. 212

- ↑ Freedman pp. 21–22; Gristwood pp. 325–326

- ↑ Freedman pp. 33–34, 22

- ↑ Freedman pp. 33; Jenkins p. 217

- ↑ Adams 2008e; Adams 2008d

- ↑ Warner p. vi; Wilson p. 246

- ↑ Warner p. ix

- ↑ Warner p. xxxix

- ↑ Warner p. xl; Adams 2008e

- ↑ Warner p. vi, vii

- ↑ Warner p. xlvi

- ↑ Wilson p. 326

- ↑ Warner pp. v–ix, xxxviii–xlvii

- ↑ Read p. 23

- ↑ Rickman p. 51

- ↑ Adams 2008c; Adams 2008d; Adams 2008e

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 234–235

- ↑ Doran p. 161

- ↑ Wilson pp. 229–230

- ↑ Hammer p. 35

- ↑ Jenkins p. 287

- ↑ Nicolas p. 382

- ↑ Jenkins p. 362

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 280–281

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 182

- ↑ Hammer pp. 34–38, 60–61, 70, 76

- ↑ Wilson pp. 228, 230–231

- ↑ Nicolas p. 97; Jenkins p. 247

- ↑ Owen p. 44; Jenkins pp. 263, 305

- ↑ Hume 1892–1899 Vol. III p. 477; Jenkins p. 279

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 280–281; Gristwood p. 380

- ↑ Jenkins p. 305

- ↑ Wilson p. 247

- ↑ Hammer p. 46

- ↑ Wilson p. 195; Haynes 1987 p. 14

- ↑ Hume 1892–1899 Vol. II p. 572; Haynes 1987 p. 14

- ↑ Haynes 1992 p. 84

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 17–18

- ↑ Doran p. 59

- ↑ Wilson p. 215; Collinson 1960 pp. xxv–xxvi

- ↑ Rosenberg p. 23

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 121

- ↑ Haigh p. 16; Doran p. 212

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 18; Alford p. 30; Doran p. 216

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 18–19, 59

- ↑ Jenkins p. 247

- ↑ Doran p. 190

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 34

- ↑ Wilson p. 217

- ↑ Wilson p. 216

- ↑ Wilson p. 215

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 104, 107

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 137–138, 141

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 18

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 159–160, 168–169

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 187

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 194–198

- ↑ Wilson p. 243

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 300, 281

- ↑ Jenkins p. 298

- ↑ Wilson p. 329; Haynes 1987 p. 156

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 323–324

- ↑ Jenkins p. 327

- ↑ Willson pp. 75–76

- ↑ Hammer p. 59–60

- ↑ Gristwood pp. 414–415

- ↑ Hammer pp. 60, 61

- ↑ Gristwood p. 376

- ↑ Wilson p. 146; Adams 2002 p. 337

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 142, 337

- ↑ Wilson p. 165

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 88–94

- ↑ Wilson pp. 164–165; Gristwood p. 257

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 145–149

- ↑ Wilson p. 169

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 250

- ↑ Wilson pp. 131–132, 168–169;

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 177–178

- ↑ Jenkins p. 178; Gristwood p. 317

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 75–76; Jenkins p. 178

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 230

- ↑ Haynes 1987 p. 77; Adams 1995 p. 212

- ↑ Adams 2008c; Rosenberg p. 64

- ↑ Wilson p. 160

- ↑ Rosenberg p. 64

- ↑ Wilson p. 153

- ↑ Rosenberg p. 305

- ↑ Wilson illustration caption

- ↑ Hearn p. 96; Haynes 2007 p. 74; Haynes 1987 p. 199

- ↑ Hearn p. 124

- ↑ Martyn pp. 37–40; Haynes 1992 p. 12

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 76–78, 125–126; Wilson p. 307

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 254–257

- ↑ Jenkins p. 261

- ↑ Chamberlin pp. 400–401

- ↑ Adams 2008c; MacCulloch p. 189

- ↑ Doran pp. 66–67

- ↑ Collinson 1971 p. 53

- ↑ MacCulloch pp. 213, 249; Adams 2002 pp. 141–142

- ↑ Wilson pp. 198–205; Adams 2002 p. 231

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 231

- ↑ Wilson p. 205

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 231, 143, 229–232; Collinson 1960 p. xxx

- ↑ Collinson 1960 pp. xxi–xxiii, xxxviii

- ↑ Collinson 1960 pp. xxi–xxiii

- ↑ Collinson 1971 p. 63

- ↑ Collinson 1960 p.xxxv

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 230–231

- ↑ Collinson 1960 pp. xxvi–xxvii; Adams 2002 p. 338

- ↑ Adams 1995 p. 463; Adams 2002 p. 190

- ↑ 253.0 253.1 Wilson p. 162

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 144–145; Haynes 1992 p. 15

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten pp. 7–15; Wilson p. 238; Haynes 1987 p. 158

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten pp. 20; 24

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 147

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten p. 25

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten p. 53

- ↑ Wilson pp. 276–278

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten pp. 55, 73

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten p. 54

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 158–159; Bruce p. 17; Strong and van Dorsten pp. 23, 25

- ↑ Bruce p. 15

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten p. 53; Gristwood p. 401

- ↑ 266.0 266.1 Chamberlin pp. 263–264

- ↑ Bruce p. 105

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten p. 59

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 274

- ↑ Bruce p. 424

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten p. 72

- ↑ Gristwood p. 408

- ↑ Bruce p. 309; Wilson pp. 282–284

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 147; Gristwood p. 396

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 180; Adams 1987

- ↑ Wilson pp. 279, 281–282

- ↑ Gristwood p. 406

- ↑ Bruce p. 339

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten p. 75

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten pp. 75–76; Haynes 1987 p. 175

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 172–174

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten pp. 43, 50

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 170–171; Jenkins p. 323

- ↑ Wilson p. 291

- ↑ Wilson pp. 291–294

- ↑ Wilson p. 294

- ↑ Wilson pp. 294–295

- ↑ Strong and van Dorsten pp. 73, 77; Wilson p. 338

- ↑ Watkins p. 167; Gristwood p. 433

- ↑ Haynes 1987 p. 191

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 349–351

- ↑ Haynes 1987 pp. 191–195

- ↑ 293.0 293.1 Hume 1892–1899 Vol. IV pp. 420–421; Jenkins p. 358

- ↑ Jenkins pp. 362–363

- ↑ Gristwood pp. 428–430; Lovell p. 355

- ↑ Wilson p. 302

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 148; Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester: Autograph letter, signed, to Queen Elizabeth I. Folger Shakespeare Library Retrieved 2009-07-17

- ↑ Wilson p. 303

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 149; Gristwood p. 437

- ↑ Gristwood p. 437

- ↑ Wilson pp. 262–265

- ↑ WorldCat Retrieved 2010-04-05

- ↑ Burgoyne p. vii

- ↑ Jenkins p. 294

- ↑ Bossy p. 126; Wilson p. 251

- ↑ Wilson pp. 253–254

- ↑ Burgoyne p. 225

- ↑ Wilson pp. 254–259; Jenkins pp. 290–294

- ↑ Adams 1996; Wilson p. 268

- ↑ Wilson p. 307

- ↑ Haynes 1987 p. 200

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 53–55

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 55, 56, 65

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 57

- ↑ Haynes 1987 p. 11

- ↑ Chamberlin p. 103

- ↑ Wilson p. 304

- ↑ 318.0 318.1 Adams 2002 p. 176

- ↑ Adams 2002 pp. 226–228

- ↑ Haynes 1992 p. 15

- ↑ Gristwood p. 479; Adams 2002 p. 2

- ↑ Adams 2002 p. 7

References

- Adams, Simon (1987): "Stanley, York and Elizabeth's Catholics" History Today Vol. 37 No. 7 July 1987 Retrieved 2009-10-10

- Adams, Simon (ed.) (1995): Household Accounts and Disbursement Books of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, 1558–1561, 1584–1586 Cambridge University Press ISBN 0521551560

- Adams, Simon (1996): "At Home and Away. The Earl of Leicester" History Today Vol. 46 No. 5 May 1996 Retrieved 2009-09-15

- Adams, Simon (2002): Leicester and the Court: Essays in Elizabethan Politics Manchester University Press ISBN 0719053250

- Adams, Simon (2008a): "Dudley, Amy, Lady Dudley (1532–1560)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edn. Jan 2008 (subscription required) Retrieved 2010-04-04

- Adams, Simon (2008b): "Dudley, Lettice, countess of Essex and countess of Leicester (1543–1634)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edn. Jan 2008 (subscription required) Retrieved 2010-04-04

- Adams, Simon (2008c): "Dudley, Robert, earl of Leicester (1532/3–1588)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edn. May 2008 (subscription required) Retrieved 2010-04-03

- Adams, Simon (2008d): "Dudley, Sir Robert (1574–1649)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edn. Jan 2008 (subscription required) Retrieved 2010-04-03

- Adams, Simon (2008e): "Sheffield, Douglas, Lady Sheffield (1542/3–1608)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edn. Jan 2008 (subscription required) Retrieved 2010-04-03

- Alford, Stephen (2002): The Early Elizabethan Polity: William Cecil and the British Succession Crisis, 1558–1569 Cambridge University Press ISBN 0521892856

- Bossy, John (2002): Under the Molehill: An Elizabethan Spy Story Yale Nota Bene ISBN 0300094507

- Bruce, John (ed.) (1844): Correspondence of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leycester, during his Government of the Low Countries, in the Years 1585 and 1586 Camden Society [1]

- Burgoyne, F.J. (ed.) (1904): History of Queen Elizabeth, Amy Robsart and the Earl of Leicester, being a Reprint of "Leycesters Commonwealth" 1641 Longmans [2]

- Chamberlin, Frederick (1939): Elizabeth and Leycester Dodd, Mead & Co.

- Collinson, Patrick (ed.) (1960): "Letters of Thomas Wood, Puritan, 1566–1577" Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research Special Supplement No. 5 November 1960

- Collinson, Patrick (1971): The Elizabethan Puritan Movement Jonathan Cape ISBN 0224611321

- Doran, Susan (1996): Monarchy and Matrimony: The Courtships of Elizabeth I Routledge ISBN 0415119693

- Fraser, Antonia (1972): Mary Queen of Scots Panther Books ISBN 0586033793

- Freedman, Sylvia (1983): Poor Penelope: Lady Penelope Rich. An Elizabethan Woman The Kensal Press ISBN 0946041202

- Girouard, Mark (1979): Life in the English Country House. A Social and Architectural History BCA

- Girouard, Mark (2009): Elizabethan Architecture: Its Rise and Fall, 1540–1640 Yale University Press ISBN 9780300093865

- Gristwood, Sarah (2007): Elizabeth and Leicester Bantam Books ISBN 9780553817867

- Haigh, Christopher (2000): Elizabeth I Longman ISBN 0582437547

- Hammer, P.E.J. (1999): The Polarisation of Elizabethan Politics: The Political Career of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, 1585–1597 Cambridge University Press ISBN 0521019419

- Haynes, Alan (1992): Invisible Power: The Elizabethan Secret Services 1570–1603 Alan Sutton ISBN 0750900377

- Haynes, Alan (2007): Walsingham: Elizabethan Spymaster & Statesman Sutton Publishing ISBN 9780750947718

- Haynes, Alan (1987): The White Bear: The Elizabethan Earl of Leicester Peter Owen ISBN 0720606721

- Hearn, Karen (ed.) (1995): Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England 1530–1630 Rizzoli ISBN 084781940X

- Henderson, Paula (2005): The Tudor House and Garden: Architecture and Landscape in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Yale University Press ISBN 0300106874

- Historical Manuscripts Commission (ed.) (1911): Report on the Pepys Manuscripts Preserved at Magdalen College, Cambridge HMSO [3]

- Hume, Martin (ed.) (1892–1899): Calendar of ... State Papers Relating to English Affairs ... in ... Simancas, 1558–1603 HMSO Vol. I [4] Vol. II [5] Vol. III [6] Vol. IV [7]

- Hume, Martin (1904): The Courtships of Queen Elizabeth Eveleigh Nash & Grayson [8]

- Ives, Eric (2009): Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery Wiley-Blackwell ISBN 9781405194136

- Jenkins, Elizabeth (2002): Elizabeth and Leicester The Phoenix Press ISBN 1842125605

- Loades, David (1996): John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland 1504–1553 Clarendon Press ISBN 0198201931

- Loades, David (2004): Intrigue and Treason: The Tudor Court, 1547–1558 Pearson/Longman ISBN 0582772265

- Lovell, M.S. (2006): Bess of Hardwick: First Lady of Chatsworth Abacus ISBN 9780349115894

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2001): The Boy King: Edward VI and the Protestant Reformation Palgrave ISBN 0312238304

- Martyn, Trea: Elizabeth in the Garden (2008): A Story of Love, Rivalry and Spectacular Design Faber & Faber ISBN 9780571216932

- Nicolas, Harris (ed.) (1847): Memoirs of the Life and Times of Sir Christopher Hatton Richard Bentley [9]

- Nichols, J.G. (ed.) (1850): The Chronicle of Queen Jane Camden Society [10]

- Owen, D.G. (ed.) (1980): Manuscripts of The Marquess of Bath Volume V: Talbot, Dudley and Devereux Papers 1533–1659 HMSO ISBN 011440092X

- Read, Conyers (1936): "A Letter from Robert, Earl of Leicester, to a Lady" The Huntington Library Bulletin No. 9 April 1936

- Rickman, Johanna (2008): Love, Lust, and License in Early Modern England: Illicit Sex and the Nobility Ashgate ISBN 0754661350

- Rosenberg, Eleanor (1958): Leicester: Patron of Letters Columbia University Press

- Skidmore, Chris (2010): Death and the Virgin: Elizabeth, Dudley and the Mysterious Fate of Amy Robsart Weidenfeld & Nicolson ISBN 9780197846505

- Strong, R.C. and J.A. van Dorsten (1964): Leicester's Triumph Oxford University Press

- Warner, G.F. (ed.) (1899): The Voyage of Robert Dudley to the West Indies, 1594–1595 Hakluyt Society [11]

- Watkins, Susan (1998): The Public and Private Worlds of Elizabeth I Thames & Hudson ISBN 0500018693

- Williams, Neville (1964): Thomas Howard, Fourth Duke of Norfolk Barrie & Rockliff

- Wilson, Derek (1981): Sweet Robin: A Biography of Robert Dudley Earl of Leicester 1533–1588 Hamish Hamilton ISBN 0241101492

- Willson, D.H. (1971): King James VI & I Jonathan Cape Paperback ISBN 0224605720

External links

| Simple English Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester |

- Dudley, Robert in Venn, J. & J. A., Alumni Cantabrigienses, Cambridge University Press, 10 vols, 1922–1958.

- Archival material relating to Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester listed at the UK National Register of Archives

- Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (c. 1531-1588), luminarium.org encyclopedia project from Encyclopedia Britannica Eleventh Edition, 1911

- Lawes and Ordinances militarie (1586) by the Earl of Leicester

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Henry Jernyngham |

Master of the Horse 1558–1587 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Essex |

| Vacant | Lord Steward 1587–1588 |

Succeeded by Lord St John of Basing |

| Preceded by ? |

Chamberlain of the county palatine of Chester 1565–1588 |

Succeeded by ? |

| Preceded by ? |

Chamberlain of Anglesey, Caernarvonshire and Merioneth 1578–1588 |

Succeeded by ? |

| Vacant | Lord Lieutenant of Norfolk 1552–1553 With: Henry Radclyffe, 2nd Earl of Sussex |

Vacant |

| Vacant | Lord Lieutenant of Warwickshire and Worcestershire 1559–1560 With: Sir Ambrose Cave |

Vacant |

| Vacant | Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire 1569–1570 With: Sir Ambrose Cave |

Vacant |

| Vacant | Lord Lieutenant of Leicestershire 1584 |

Succeeded by ? |

| Vacant | Lord Lieutenant of Essex and Hertfordshire 1585–1588 |

Succeeded by The Lord Burghley |

| Preceded by Sir John Salusbury |

Custos Rotulorum of Denbighshire bef. 1573–1588 |

Succeeded by Thomas Egerton |

| Preceded by John Griffith |

Custos Rotulorum of Flintshire bef. 1584–1588 |

|

| Preceded by Sir Ambrose Cave |

Custos Rotulorum of Warwickshire bef. 1573–1588 |

Succeeded by Sir Fulke Greville |

| Preceded by Maurice Wynn |

Custos Rotulorum of Caernarvonshire bef. 1579–1588 |